The Soul's Engine

What Moves Us Towards God?

Everything has an engine, something that powers it. Athletes with high drive and high energy are said to have a big “motor.” Even something as simple as a mousetrap has a spring that provides the energy to make it work. Without an engine, there’s no power in the machine. So, what’s the engine, the motor, or more precisely, the motive center of the human soul?

Before we can answer that question, much like a mousetrap, we need to understand the soul’s constituent parts and how they work together: namely, the mind, will, heart, and body. Different thinkers within Classical Western Theism tweak that assembly, but from Aristotle, these fundamental constituent elements remain.

As we consider each of them briefly, we see that the mind is the center of cognition. It’s the thinking faculty of the soul, where reason and logic hold sway. The will is the volitional center, the “doing” part of our humanity. The heart is known as the seat of our affections, or our desires. These are often conflated with feelings, which is unfortunate because they run deeper and mold us more fundamentally. The body? That’s perhaps the most obvious of the group. It is our physical being, distinct, but inseparably related to the other three.

Working Models

Before we can return to our original question (What is the motive center of the human soul?), we need to understand how key parts work together. For example, we might have all the necessary pieces for a mousetrap at our disposal, but if we do not grasp how they work together, we will never comprehend a real, working mousetrap. In the same manner, we can understand the fundamental parts of the human soul, but if we do not grasp how they are designed to work together, we will be left with a faulty spiritual anthropology. If that’s the case for us as pastors, we will also be largely ineffective at helping people become spiritually formed into healthy, mature Jesus Followers.

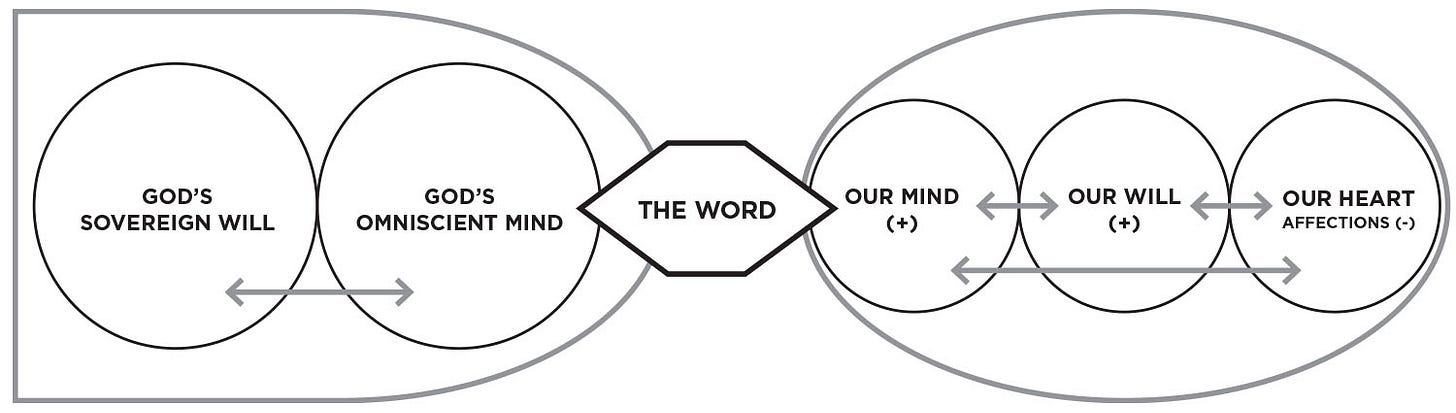

Two basic working models of the soul underlie contemporary spiritual formation. The first can be termed Classical Western Theism. Deeply influenced by pagan philosophy, it comes to us from Aquinas, with an assist from Aristotle. Its influence is broad and deep, and axiomatic to someone like Dallas Willard’s views, for example. The following diagram illustrates how the constituent faculties of the soul work together in this model. According to its view, mature spirituality can be measured by our good moral choices.

All three faculties motivate our choices, producing a multi-directional inward “conversation.” The mind and will are the more noble faculties since they represent qualities inherent in “God.” Conversely, the affections, by their nature, are unstable. The affections are further suspect as the source of temptations, because they allegedly respond poorly to external ethical stimuli. They also lack a counterpart in God who is necessarily The Unmoved Mover.1 God is therefore impassible and not subject to passions or desires, at least according to Classical Western Theism.

Good moral choices require the mind and the “free” will to work in tandem to overcome the unreliable affections. Within this model, the Christian’s will is thus “enabled” by grace, an inhabiting quality of the human soul.

You don’t have to search far to see how this view of spiritual formation dominates our day. From Aquinas to Willard to Foster to Comer, you see the “disciplines” employed to shape one’s “habits,” which in turn form the person. Grace is the spiritual gasoline that enables us to overcome unstable passions via the “renewed mind” and the empowerment of our will. You see it more commonly in the battle cry of young parents dropping their kids off for whatever while crying, “Make good choices!”

Many pastors, writers, scholars, and theologians embrace and endorse this model. So, isn’t that a good thing if so many experts believe it’s true? Not necessarily. Despite Cole Porter’s assertion that "Fifty Million Frenchmen Can't Be Wrong," they can be. The mere fact that a majority of people believe something is true does not guarantee its veracity.

Fortunately, there is an alternative that finds greater purchase in the Scriptures, at least in my view. It’s known as The Affective Model, or a heart-based theological anthropology:

This model2 functions differently: each faculty of the soul works through its successor in a linear fashion, from the heart to the hands. The heart, the seat of our affections (or, “desires”), evaluates external stimuli according to one’s strongest loves. The mind uses the heart’s evaluation (or values) to make its informed judgments (i.e., processing its options). And finally, the will applies the mind’s best judgment and takes action. In this view, the efficacy of responsive love becomes the meter of spiritual formation.

A key difference between this view and the first model is the belief that all choices flow from the inclination of one’s heart, the seat of one’s affections (Proverbs 4:23). Critics of this model will point to Bible references about our instrumental faculties, like thinking or choosing. However, a closer examination of such passages usually reveals the larger context: a presumptive affective, or warm-hearted love for God at work.

Christ made the centrality of the heart’s desires clear in several settings when He spoke of the heart as the source of evil thoughts and choices (Mark 7:5-23; also see Paul’s application in Eph 4:17). Jesus’ warnings in the Sermon on the Mount from Matthew’s Gospel futher illustrate that moral guilt is based not simply on the external behaviors of adultery or murder, but on inward motives of the heart, even in the absence of those unlawful actions.

Building on a Rock

So, why does this matter? Consider for a moment that you’re trying to build a house. You want the structure to be stable and safe for its human inhabitants. Not only will you construct a solid foundation, but you will also rely on assumed truths about the nature of reality, namely, that gravity is real and works in a well-understood manner. Without that underlying assumption, the accumulated wisdom of your local building codes is useless. Every building technique you’ve ever learned for safely supporting the weight of an enclosed structure — and the materials required to do so — no longer applies. It would be like trying to build in space, where everything is weightless.

Now, imagine that everything you assume about how the human soul works is flawed. It rests on a mash-up of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics with a systematic Medieval theology rather than on the Bible. That’s the problem with Classical Western Theism, which is still the “gravity” for most contemporary spiritual formation in the Western Protestant Evangelical tradition.

The following diagram summarizes the stark differences between these two models: Aristotelian (Classical Western Theism) and Affective, or heart-based. It includes their views on major categories of doctrine and spiritual formation. It also features a third, less dominant mystical option that lies beyond the scope of this post.

Separate Streams

When I discuss this summary diagram with colleagues, they often suggest combining the streams. I get that. For example, Eugene Peterson embraces the disciplines so central to the Aristotelian model. Even so, his writing demonstrates a more profound influence from the biblical, affective view of the human soul — in other words, by the indelible impact of God’s love upon his heart.

It’s not possible to read authors like Peterson, Ray Steadman, Henri Nouwen, or Bernard of Clairvoux without feeling how deeply each has been shaped as a responsive, beloved theophilus, a beloved friend of God. Though water from the other streams might leak onto their work, they remain firmly in the current of God’s “river of delights” as Psalm 36:8 puts it.

The language of Psalm 38, and indeed most of the psalms, is notably affective, aimed at the heart. Why? As God inspires Jesus’ prayer book, maybe He wants to ensure that it would ring with the language of the heart, considering its importance to His Son’s formation (Luke 2:52).3 The poetry of the Psalms assumes that our affections are fundamental to our connection with God. As His “beloved children,” (Eph. 5:1), we connect heart-to-heart. Considered as a whole, the Psalms argue for the middle stream illustrated above.

Is This the Heart of the Matter?

As I’ve argued, the heart is the soul’s engine. As such, it’s vital to our sense of how we’re connected to God. The heart’s place and efficacy in that connection will vary depending on which model we subscribe to. Consider the following conceptual diagrams, which address the question: How does a human soul engage with God?

This model corresponds to Classic Western Thesim’s view of the soul’s operation. The most striking feature is the absence of the “heart” on the left. Why? Because one of God’s key attributes4 is impassibility. In this view, God has no faculty for the notoriously unreliable affections. They are an affront to the model’s Aristotelian influence by way of the Unmoved Mover.

Classic proof texts in defense of this view include Romans 12:2, “...be transformed by the renewing of your mind.” And, John 8:31-32, “...you will know the truth and the truth will set you free.” Presumably, through an enabled mind-will operation. God’s revealed Word, both written and enfleshed, transmits from mind to mind. God wills something, communicates that rationally to our minds, and our mirrored rationality directs our will, though imperfectly apart from “grace.” God’s rationality dominates the conversation.

Forgive me if this is your view, but doesn’t “God” seem more like Star Trek’s Spock rather than Jesus according to this model? The next model illustrates a profoundly different, affective operation.

In this view, God’s Heart becomes prominent. Why? God’s love is no longer an intellectualized abstraction but a real passion that elicits a corresponding response in the human soul. When we encounter the divine nature as love5, it is not simply an accommodation of His self-revelation. It is real, as real as anything can be, shared within the Triune God, Father, Son, and Spirit. It is this Third Person, the Spirit (Spirit of Christ6, Spirit of Love7, Spirit of Truth8, all biblical language), who discloses God’s love directly to the human soul, in concert with the Word, both written and Incarnate.

Our hearts are thus stirred to responsive love. We are remade at the heart level (Ezekiel 36:26-28), with a warm inclination towards God as beloved children. Notice how Ezekiel casts this renewal within a restored relationship (v28). He surely has in mind God’s love, as depicted in Exodus 34:6-7, Deuteronomy 7:9, the erotically charged language of Ezekiel 16, and Zephaniah 3:17, whose passionate language defies abstraction.

We also see this in the Gospels, where perfect divine love intersects with re-created humanity in Jesus. Every compassionate encounter Christ has with desperate people argues that God’s love is more than an intellectual conception. It is real, and beats within a warm heart.

Paper-Thin Discipleship

Perhaps this is why so many Christians are frustrated with their spiritual formation. They lack an abiding sense of real heart-to-heart connection with God, all while growing weary of working at the “disciplines.”9 They buy popular books and write their “rules of life,” but they experience precious little soul-deep transformation.

Something is missing from a formative experience of God’s love.

Think about it. If you’re a pastor, how many of your people are truly thriving because they’ve embraced an approach to spiritual formation that rests upon the first model noted above? I’m not talking about a few months of infatuation with Practicing the Way, but a decades-long, joy-filled fruitfulness. I’d wager it’s not many, which is why Comer can sell a book based on the same work that Willard and Foster did decades ago, preceded by Aquinas and Loyola before any of them.

Because the outside-in, mind-and-will approach doesn’t work, not well or for very long, no matter how many times we try, unless it’s undergirded by an implicitly affective approach to spiritual formation.10 I’m not arguing from pragmatism here. Just because something works doesn’t make it true, but if something is true, really true, it should work, right?

Now, dear reader, think about the most winsome, mature, and Christlike Jesus follower you know. What marks their life? I’d wager it’s love. They love deeply and well. They love God and others as Jesus modeled (Mark 12:28-31). I bet their heart oozes God’s love. Why? Because the Spirit inhabits and enlivens the engine of their souls, i.e., their hearts. No matter how difficult their circumstances, the Presence of God’s love is unmistakable. They are living examples of the heart’s centrality as offered to us by Saint Paul in Romans 5:3-5.

Practical and Pastoral

Obviously, I’ve opened a huge can of worms, challenging the likes of Aristotle, Aquinas, and Willard. My goal is not to throw shade at these men or to write comprehensively about (or even adequately sketch) an affective theology. It is merely to set the table for your exploration of a heart-based pastoral theology that, when practiced, helps us shepherd people into lasting, mature, and deeply spiritually-formed disciplemaking. After all, that is our mission (Matt. 28), yes?

Consider my friend’s example. A fellow pastor, he wandered into my office one day while I was working on the diagrams above. Noticing the characterization of sin in the Augustinian stream, he said, “I use that all the time.”

When I asked him how, he replied with this story. A young man came to him for pastoral counsel, asking, “Is it a sin to smoke weed?” It’s an understandable question in Oregon, where we live. Recreational marijuana consumption is legal for adults, and Christian liberty arguably allows for the responsible use of legal intoxicants.

Side-stepping the question of federal law, my friend wisely asked, “It depends on how you define sin. Who gets hurt when you smoke weed? Are any relationships violated?”

The young man’s shoulders slumped while he admitted that his wife hated it. The conversation turned to matters of the heart — not to the exclusion of behaviors, but as their source. My wise fellow pastor worked with this man, assuming the affective model was real, and applying it to a spiritual formative pastoral conversation with dramatic effect. The young man got it. At issue was not the legality of his behavior but the destructive relational waves that it generated.

Bothered by This Model?

Despite the biblicism and effectiveness of the affective model, there will be folks for whom this post is disturbing. I say to them, “I get it.” When I first encountered these ideas, I was unsettled by them. I spent decades being told that my will was the most important part of my soul, which spawned this corollary: if you sin, your mind and will are weak, so try harder. In my worst moments, I could only assume that the problem lay with me. God had done all He could to aid me, but I was too flawed ot make good use of His “grace.”

However, when I discovered that my behavioral struggles were related to a series of competing and incompatible desires, or affections, I realized that the problem was the seat of those affections, my heart. As C.S. Lewis writes:

“It would seem that Our Lord finds our desires not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too easily pleased.”

That rang true. I was “far too easily pleased.” That realization gave me a profound sense of freedom and a new spiritual vitality.

I no longer needed to work hard at reordering the disordered desires of my heart. I needed to embrace God-given, deeper, and stronger holy desires granted to me by my Savior when I was “born from above.” My spiritual growth was no longer tied to trying harder (granted, with divine help) to exercise my mind and will in a battle for sanctification. Instead, I was invited to sink deep into God-given passions, designed to be so much more attractive. It seemed to me that God's method, where robust, godly desires would overcome weaker, sinful desires, offered better traction.

Walking in step with the Spirit became a matter of embracing the identity I was given along with these new desires. Even this was couched in affective terms. I was God’s beloved friend11 (John 15:5); I was given to know His heart. My blessed obedience as a follower found its source in love: God’s heartfelt love for me and my responsive love for him (John 14:15). Within this context, Jesus promised to share intimacy (John 14:21). All of this was, and remains, deeply warm-hearted, relational, and highly formative.

Those who disagree with me might claim that my argument is entirely subjective. They’re right in the sense that my experience was my starting point, but it doesn’t mean that I’m wrong. I believe I’ve demonstrated in brief that Scripture and practice lend strong support to the affective, heart-based view I’m arguing for.

Let Go and Abide

Dr. Ron Frost, a colleague, teacher, and mentor of mine, once shared a story with me about a noted theologian, a proponent of Classical Western Theism, who claimed that all theology had to revolve around the glory of God rather than the love of God. This theologian argued this way because God must remain impassible. A collection of attributes, each one requiring a vigorous defense, drove his theological conception of God. That’s often the rub. We have theological touchstones that we want to preserve. These prevent us from considering reasonable, biblical alternatives, like the model I present in this post.

That’s why metaphors matter. They communicate at a deeper level than simple, dispassionate, and rational rhetoric. They slide helpfully between the seams of our theological walls. That can be bad if the metaphor or storyteller is unholy. However, as C.S. Lewis once wondered, commenting on the power of imaginative literary devices to bypass our rational or emotional inhibitions, “Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons?”

Jesus understood the power of story and metaphor. He employed them in a trustworthy manner, and as much more than mere accommodation to his first-century listeners. If we agree that God’s Spirit inspires all Scripture, then all gospel metaphors are still powerfully instructive for us in our context. When Jesus says to abide in Him so that we might be fruitful, we must pay attention when He unpacks “abiding” with a branch and a vine metaphor.

Let’s consider that along with one of Paul’s fruits of the Spirit, namely, self-control. At first glance, this particular fruit would seem to be related almost entirely to the exercise of one’s will. We know what we should do, so let’s “just do it,” as our friends at Nike recommend.

Certainly, our experience of self-control appears to us psychologically as an act of our will. And there is no doubt our will is operative. However, Jesus teaches that an organic and perichoretic relationship (vine and branch) with Him is key to producing good fruit. While that clearly applies to disciplemaking, given the context in John’s Gospel, it must surely also be relevant to spiritual formation. These two, disciplemaking and spiritual formation, are distinct but inseparably related.

Therefore, the most fundamental ground for realizing an abundant harvest of self-control is, in fact, an abiding relationship with Jesus characterized by mutual love. Notice that this principle applies more broadly. For example, when Jesus restores Peter, He makes the apostle’s love for the Messiah the most foundational qualification for a fruitful and faithful ministry: “Simon, …do you love me? Then…” Jesus does this, despite Peter’s self-awareness that his responsive love for Jesus will never be as deep and profound as the Savior’s love for him. It’s not a quid-pro-quo. It’s the Vine and His branches.

Moreover, the fruitfulness of a branch works at a sub-rational, involuntary level. As long as the branch remains connected to the vine, abiding within the identity and relationship for which it was created, the branch remains fruitful. It doesn’t have to think about it or try hard. This is where the metaphor breaks down, though, as does all such figurative language. Branches and vines do not have minds and wills. We do.

However, Jesus’ metaphor is designed to uncover a deeper “abiding” than mere cognition and volition. A connection that, as I’ve argued above, is a heart-to-heart, love-to-love connection. That motive engine works through the mind and eventually fuels the will, but it is primary to both.

Conclusion

I’ve argued that the heart is the soul’s engine because, as the seat of our affections, our loves, it is the soul’s motive faculty. This corresponds to God’s self-revelation. At a foundational level, the Triune God’s nature is one of interpersonal love. This is the Trinitarian engine that manifests as God’s endlessly creative, committed, covenantal love for His Creation, especially humans. Since we are created in God’s image, it follows that our internal engine would also be divine love poured out into our hearts by the Holy Spirit, who is given to us.

This is the love that enfleshed Jesus for all eternity and took Him to the Cross. God was motivated by His love for us: He loved us “in this manner,” selflessly, lovingly giving us His only Son.

In response, we love Him who first loved us with all of our hearts. And then, as Augustine said, “Do what you want.”

Addendum

When I share my views as I have in this post, I’m often asked, “So, are you opposed to the disciplines, then?” My answer is always, “No, but it depends.” The question is this: How do we understand the value of the disciplines, or spiritual practices, which is a term I prefer? Consider this illustration.

My wife and I have been married for more than 40 years. By all accounts, we have a good marriage. Not perfect, but good. Part of the credit for that goes to a “discipline” we have embraced. Once a week, we go out and share a meal. Most often we cook at home and eat together, but this one night is special. It affords us more time to connect, freed from the labor of preparing and cleaning up after the meal.

Most of those nights are really good. The pace is slow, we talk about soulful things, encouraging and even challenging one another. All of that deepens the intimacy and trust we share. However, imagine if we go to a place that has tons of screens, each playing a different sporting event. What if I spend most of our time together eyeballing those screens, and my wife dives into her phone, texting friends and other family? Technically, we would have practiced our discipline, but to a very different effect. In fact, we’d likely damage our relationship, even if minimally. So, the mere check-the-box performance of a discipline isn’t helpful and is arguably harmful.

This is where the disciplines can be tricky, because many of their proponents smuggle in an Aristotelian view of character formation: external habits performed repeatedly will shape our character. Admittedly, there’s a certain pragmatic utility to that view. For example, the military is good at producing preferred and repeatable behaviors based upon its training, or “disciplines” if you prefer.

Here’s the rub: the Christian life is not primarily about preferred and repeatable behaviors.

However, from Ezekiel’s monumental passage on regeneration to Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, the Bible reverses that Aristotelian flow. Formation runs from heart to hands, not hands to heart. Jesus said, “Apart from me, you can do nothing.” If the disciplines, or spiritual practices, nurture an abiding heart-to-heart connection with Jesus — our trust in Him and our responsive love towards Him — they can help us stay relationally connected to Him. But they are only scaffolding. They are not the beautifully constructed home and table, filled with warmth, and food, and love. They can be supportive, but only the loving Presence of Jesus is formative.

The Unmoved Mover is Aristotle's concept of a first cause that initiates all movement and change in the universe. Thomas Aquinas was influenced in his conceptualization of God by this idea, and later incorporated it in his cosmological arguments for God’s existence.

This diagram and all others in this post are adapted from (and draw heavily upon) those designed by Dr. Ron N. Frost, a friend and professor of mine. You can read him at his blog Spreading Goodness.

The divine Person, Jesus of Nazareth, developed as any human would, and the Gospels lend ample support to the centrality of major prophets, like Isaiah and Daniel, along with the Psalms, to Jesus’ sense of identity and mission.

“Attributes” is the traditional language for describing God and is telling, as if humans can fully grasp God’s revealed perfections and attribute them to Yahweh.

1 John 4

Romans 8:9

2 Timothy 1:7

John 14:17 and John 16:13

To understand this weariness, read Brother Lawrence's Practicing the Presence of God.

Again, Brother Lawrence is instructive. He characterizes the most productive and satisfying spiritual life as a continual loving conversation with God. He also sees the disciplines yielding minimal value, almost as if they were training wheels to be readily discarded early in the process.

Or child, etc., note the persistent familial, relationally rich language throughout Scripture